The Seatbelt Saga: Volvo’s Pioneering Legacy

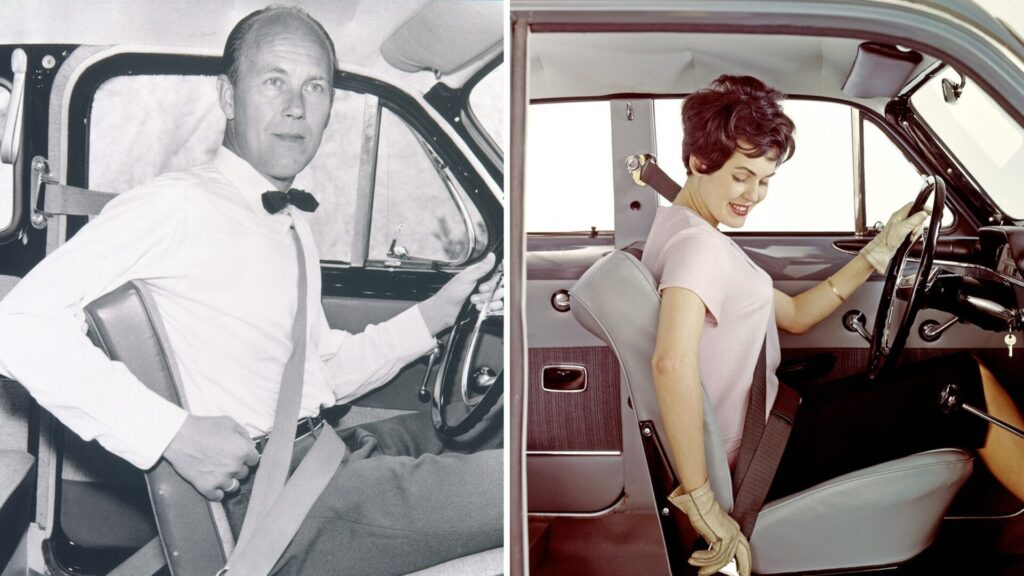

When Volvo introduced the three-point seatbelt in 1959, they made an unprecedented move: they made the patent available for free to all competitors. This decision was driven by a profound commitment to saving lives, valuing the seatbelt as a universal life-saving tool rather than a profit-generating product.

Volvo’s innovative spirit dates back to 1959 with the introduction of the three-point seatbelt, a development that remains underappreciated. Car manufacturers have a penchant for inside jokes, as seen with the seven-bar grilles on Jeep Renegades, the “groundspeed” tag on Mustang GT’s speedometers, and the tiny car on Aston-Martin Lagonda’s circuit board—a detail only a mechanic might chuckle about before handing over a hefty bill.

In the Volvo XC90, there’s a hidden message on the seatbelt buckle: “Since 1959.” This nod to Volvo’s history references a pivotal year when ex-Saab aerospace engineer Nils Bohlin designed the three-point seatbelt. Bohlin, known for his work on ejector seats for aircraft (imagine if those had been a feature in cars—“fiddle with my radio presets, will you? EJECT!”), applied his expertise at Volvo to create a simple, effective safety device made from a single length of nylon.

The breakthrough came when Volvo, despite holding the patent, chose to release it freely to other manufacturers. This decision took years to gain widespread acceptance, but it ultimately led to the adoption of the design across the industry, saving countless lives. However, there remains potential for even more lives to be saved if the seatbelt’s benefits are fully utilized today.

The seatbelt’s history mirrors the complexities of human nature. The earliest safety harnesses can be traced back to the first aircraft built by Sir George Cayley, who flew it in Yorkshire. Long before the Wright brothers took to the skies, Cayley was experimenting with aerodynamics and testing his theories by launching himself down stairs. As his glider neared perfection and he approached 80, he let his coachman test it, resulting in a famous remark: “I wish to give notice. I was hired to drive, not to fly!”

These historical anecdotes underscore the evolution of safety measures. In aviation, lapbelts and harnesses quickly gained acceptance as crucial safety features. However, in the automotive world, seatbelts were initially met with skepticism. The prevailing belief was that being flung clear of a wreck was preferable to being trapped in a burning vehicle. Early racers, such as Barney Oldfield—who first exceeded 100 km/h—wore safety harnesses, but this was not the norm.

The 1920s and 1930s saw high fatality rates in car crashes, prompting some medical professionals to advocate for safer vehicles. Despite this, public interest in safety features was limited; a belief persisted that a car with excessive safety innovations implied inherent danger. Even Preston Tucker, who pioneered the Tucker Torpedo, initially equipped his cars with seatbelts but later removed them, swayed by these misconceptions.

After World War II, car ownership soared and so did speeds, especially with the advent of new interstates. By the early 1960s, seatbelts began appearing more frequently in passenger vehicles, though they remained optional. The turning point came with Ralph Nader’s 1965 critique, Unsafe at Any Speed, which played a significant role in making seatbelts mandatory in many places, marking a new era in automotive safety.