Scientists Are Surprised to Find Out That Many Australian Mammals Glow Under UV Light

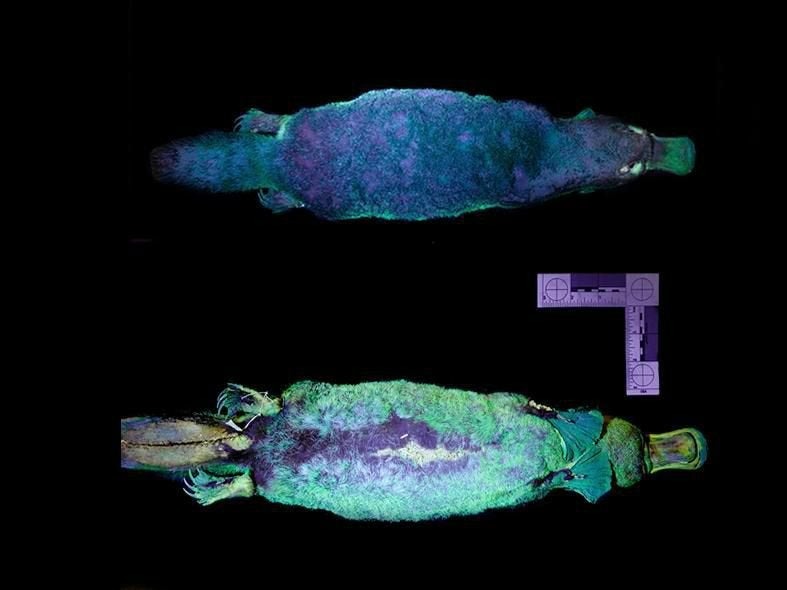

Following the accidental discovery by U.S. scientists that platypuses glow under UV light, further tests by Australian scientists have shown that other mammals, including marsupials, also glow.

After reading a paper in Mammalia reporting on platypus’s unexpected nightglow, Dr Kenny Travouillon of the Western Australian Museum decided to do a little experiment. As curator of mammals, he had plenty of dead mammals in his care and so he decided decided to turn UV light on some of them to find out whether they would also glow in the dark.

To his surprise, many of them did. Travouillon reported on the results on the museum’s social media sites. According to his findings, not only do echidnas, the platypus’s closest surviving relatives, light up under UV, but so do bilbies’ ears, possums, some Australian bats, and the popular favorite, wombats. Others then shared their own findings, including reports of glowing Tasmanian sugar gliders and eastern barred bandicoots.

Biofluorescence has long been known to occur in some insects and sea creatures, but it was unknown that it occurred in many Australian mammals, too. That said, the trait is not universal to Australian native mammals. For example, none of the kangaroo family Travouillon tested showed any color response to UV light, and a variety of other animals remained similarly dark.

After reading Travouillon’s tweets, researchers from Curtin University contacted him about teaming up for a more systematic study. They hope to provide answers as to why some marsupials have this strange trait and others don’t.

In the meantime, however, Travouillon shared with us his working theories. None of the carnivorous marsupials, including quolls and Tasmanian devils, he has tried illuminating have glown in response. He thinks this could be because such a light show would alert potential prey to their presence, particularly at twilight. Even though prey animals might appear to have even more to lose through visibility, color-blindness is common among predators, which could leave small mammals safe to glow in peace.

“Kangaroos don’t need color to see each other because they live in mobs. The solitary animals need to be able to recognize each other in mating season,” Travouillon said. It’s unclear though how this theory explains the mix among exceptionally sociable bats, and Travouillon himself stresses that further testing will be needed before a real explanation can be offered.

Travouillon also doubts that platypuses use their glow as a mating signal, noting they close their eyes when underwater. Instead, he thinks it’s probably a legacy left over from some ancient ancestor, much like humans’ vestigial tailbone.

Some bioluminescent animals produce their own light, but Travouillon saw no sign of this in the specimens he examined. They are more likely to be biofluorescent: “I think their fur just reflects UV light in a particular way, it’s probably its chemical composition.”

The fact this widespread marsupial trait has gone unnoticed until now is surprising as scientists have been aware, since as long ago as 1983, that North American opossums produce psychedelic colors under UV light.

Travouillon explains that in a pre-Internet era such findings were easily missed, which is underscored by the fact that the opossum paper is still not online. So what could have happened was simply nobody got the stimulus to see if the same thing was true in the marsupials’ homeland. Until now.